I’m still trying to decide what I should write about here. More about my PhD research? Review some of my favorite books from this year? Share what it’s been like to live on a sailboat? Partner with my brother to travel to somewhere exotic and do a photo-essay? Explore the nitty-gritty of cheese making? All of the above?

Today I want to write about trees.

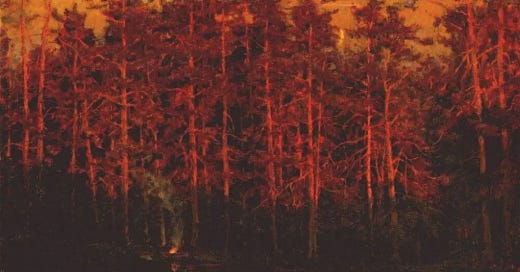

A few months ago at a dusty basement bookstore in Ulyanovsk, I bought a book of paintings by an obscure Soviet artist. The book didn’t seem all that special, but one of the paintings had caught my eye.

I was the only shopper in the bookstore. In the back room behind a curtain the owner was hosting a birthday party, and the sounds of bad pop music and “here, have some salad” and of liquid splashing into a glass could be heard filtering through the rows of shelves. It was one of those bookstores I’ve encountered only in Europe — a dim, dark basement filled with heaps and heaps of books piled on shelves, floor, and tables — old ones, new ones, prerevolutionary classics in old stitched bindings and cheap 90s paperbacks touting conspiracy theories on their covers.

Anyhow, one of the paintings in this book had caught my eye.

It was called Poslednii Luch — the Last Ray. The artist’s name was Nikolai Romadin. A stand of pines on the edge of the Volga, all colored deep red by the last ray of the setting sun. The trees crowd the canvas, their tops cut off by the frame. The river, too, is cut off, so that it could be a swamp or a pond. In the bottom third is a small campfire, but I didn’t see it until I found a higher quality version of the painting online. The trees are the subject and the focal point. The moon seems to be rising through the trees, and the sky behind them is bright.

I am still trying to understand what moved me so much about the painting as I stood there breathing in the dust and listening to tinny pop music. The date is 1945. The end of the War, the end of a whole generation. Does this painting say anything about victory? Maybe not, but it is all about the passage of time, and everything hangs on a thread: in just a few seconds that last ray will be gone, but the light of the fire will stay, twinkling in the darkness — a beacon of hope and of warmth.

I don’t like sunsets. They make me sad, somehow. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince used to scoot his chair along the asteroid where he lived to see multiple sunsets in one day. He liked to watch the sunset when he was sad, almost like a comfort.

“One day," you said to me, "I saw the sunset forty-four times!"

And a little later you added: "You know — one loves the sunset, when one is so sad..."

"Were you so sad, then?" I asked, "on the day of the forty-four sunsets?"

But the little prince made no reply.”

But for me it is the opposite — I feel no urge to follow the sunset, or even to photograph it. I prefer golden hour.

But Romadin’s painting isn’t a sunset, is it? It’s that last moment before the sun sets, when the trees and sky are still filled with light. It feels solemn, almost like a prayer. It is an ode to light.

I bought the book. A few days later I encountered more pines, on canvases in museums in the northern port of Archangel. At the Art Museum of Arctic Exploration, I wandered past paintings of forests in summer and in winter, at dawn and at sunset, covered with snow or moss.

Nothing was really going on in most of these paintings. Most of them were by the Soviet artist A.A. Borisov, who, in addition to trees, loved painting the colors of arctic snow. There were no people. No famous places. Just trees, and lots of them. And yet I wanted to stop and linger in front of every single one. There were hundreds of them.

I don’t think there’s a European equivalent (at least not a Western European equivalent) to these forest paintings. The European nature painting is more often a landscape with some demure cows and a shepherd (plenty of those in Russia too, of course) or an impressionist harbor in the fog. Then there are the beautiful American and Canadian wilderness paintings (like the Hudson River School or the Group of Seven), but they tend to be majestic craggy mountains or river valleys seen from afar. But these Russian paintings are neither majestic nor breathtaking, it’s just the forest, right in your face.

It’s true, some of the paintings by the Canadian Group of Seven do make the forest their subject. But the style is so different that there’s no direct comparison.

What is the Russian obsession with forest? Maybe it’s just the result of having so much of it. And it’s not just the birches, which have been immortalized in songs and poetry, and folk proverbs.

In Nikolay Nekrasov’s poetry, trees are tied to human fate:

Буря воет в саду, буря ломится в дом,

Я боюсь, чтоб она не сломила

Старый дуб, что посажен отцом,

И ту иву, что мать посадила,

Эту иву, которую ты

С нашей участью странно связала,

На которой поблекли листы

В ночь, как бедная мать умирала…The storm moans in the orchard, the storm breaks into the house,

I am afraid, lest the storm break

The old oak, which father planted,

And the weeping willow, which mother planted,

That willow, which you

Strangely tied to our fate,

On which the leaves turned pale

The night that poor mother was dying….1

I could offer a forest of examples, from poetry and novels, or from Chekhov’s plays, in which the characters are often thinking about trees, worried about trees as much as they are worried about each other.

And then there are short stories like Varlam Shalamov’s “Resurrection of the Larch,” about a Siberian pine which becomes a metaphor for the ultimate Russian story itself. This story is so wonderful, so heartbreakingly beautiful, that I feel I must quote it at length:

A man in the Far North seeks an outlet for his sensitivity — still not destroyed, still not poisoned even by decades of life in Kolyma. A man sends a parcel by airmail: not books, not photographs, not verse, but a larch twig, a dead twig of living nature.2

Kolyma was one of the GULAG locations, a prison camp for forced labor in the icy north of Siberia. In Shalamov’s story, one of the inmates there, having miraculously survived for decades, mails a twig from one of the trees surrounding the camp. The twig travels thousands of miles to Moscow, where an unnamed woman places it in a jar of water:

It is placed in a jam jar filled with evil chlorinated, antiseptic Moscow tap water, water that itself, perhaps, is also glad to dry out everything living — deadly Moscow tap water.

The significance of the tap water escaped me the first time I read the story. There is something deeply ironic about the symbolism here. Moscow is the prosperous city that inmates at Kolyma can only dream about seeing someday; it is still the city (like New York) that people from all over Russia dream of moving to. But in this tale even the water there is poisoned. Yet the little twig of the larch is bent on survival.

Submitting to passionate human will, the twig gathers all its strength — physical and spiritual, for a twig cannot be resurrected from physical forces alone: the Moscow warmth, the chlorinated water, the indifferent glass jar. In the twig, other, mysterious forces are awakened.

The religious imagery is too obvious here to pass over, but it becomes even more obvious in the next paragraph.

Three days and three nights pass, and the woman is woken by a strange, elusive smell of turpentine, a weak, faint smell, a new smell. In the coarse wooden bark there had appeared, emerged clearly into the world new, young, living, bright green spines of fresh pine needles.

The larch is alive, the larch is immortal, this miracle of resurrection cannot but be — for the larch was placed in the jar of water on the anniversary of the death in Kolyma of the woman's husband, a poet.

Shalamov, the author, was himself a poet. Did he have a woman waiting for him in Moscow during the seventeen years he spent in the camps? I don’t know enough about his life. But the woman is not the main subject of this story, nor its heroine. The hero of the story is the tree (how many stories are there in which the main character is a tree?) and the main action performed by the tree is religious — a resurrection after three days and three nights in a chlorinated jar of water.

The smell of the larch was weak but clear, and no force in the world could have dampened that smell, nor extinguished that green light and colour.

For how many years — warped by the winds and the frosts, twisting in search of the sun — had the larch every spring stretched its young green needles into the sky?

How many years? A hundred. Two hundred. Six hundred. The Daurian larch reaches maturity at three hundred years.

Three hundred years! The larch, whose twig, whose shoot is now breathing on a Moscow table, is the same age as Natalya Sheremeteva-Dolgorukova, and can recall her sorrowful fate: the vicissitudes of life, fidelity and constancy, spiritual fortitude, physical and moral torments that differ not at all from the torments of nineteen thirty seven — the torment of nature's fury in the North, with its hatred of man, with its mortal dangers of spring floods and winter storms, the torment of denunciations, the crude despotism of the authorities, the deaths, the quartering, the breaking on the wheel of a husband, a brother, a son, a father, who denounced each other and betrayed each other.

Is this not the perennial Russian narrative?

After the rhetoric of the moralist Tolstoy and the furious prophecies of Dostoevsky there came wars, revolutions, Hiroshima and concentration camps, denunciations, shootings.

The larch dislocated time-scales, put human memory to shame, reminded one of the unforgettable.

Is this not the perennial Russian narrative? Nature’s fury, the northern winter, and a small twisted larch tree stretching its young needles to the sky.

Is the perennial Russian narrative the Resurrection? (I think of Crime and Punishment, War and Peace, Andrei Rublev, even more recent classics like Zuleikha Opens her Eyes). For long centuries, the rhythm of every year pushed relentlessly towards the spring feast of Pascha, the Resurrection, the day when all the church bells pealed joyfully, when a small candlelit procession led by a young by with a lantern shone light into the still-cold darkness of midnight. The significance of this feast was so great and its roots were so deep that it kept on sprouting in literature just like Shalamov’s larch tree, decades after the Soviet Union had removed Pascha from its calendars. How could someone like Shalamov, confined to seventeen years of hard labor for a crime that would have gone unpunished in almost any other country — how could he keep believing in that narrative? How could he keep writing?

Was Romadin’s painting also about victory? Is that little campfire a symbol of the Paschal lantern? I don’t know for sure, but Shalamov’s little larch tree certainly is. The victory of something small and alive that wants (needs) to grow. I felt that Romadin’s The Last Ray was somehow an ode to light, a prayer. That there was something religious there. In Shalamov’s story the religious nature of the tree is too obvious to ignore, and its resurrection (a resurrection that trees all over the world undergo every spring) is the ultimate victory.

In Kolyma, writes Shalamov, nothing smells. Even the flowers have no smell.

And only the larch fills the forest with its elusive smell of turpentine. At first it seems like the smell of decay, the smell of the dead. But if you look and inhale this smell more deeply, you will understand it is the smell of life, the smell of resistance to the North, the smell of victory.

This same resistance, the same victory, was captured in a series of paintings in the Stepan Pisakhov museum in Archangel, which I visited after the museum of Arctic Exploration. Pisakhov was known for his storytelling, but also for his paintings of the arctic and of trees. There is even an art history term (confined, I’m sure, to Russian textbooks): the “Pisakhov pine.” In each of his paintings, a foreground dotted with spindly, wasted pines is broken by one tree that stands above the rest. One tree that, despite the cold, the dark of the arctic winters, and the poor soil — manages to thrive, reaching its boughs toward the sun.

Maybe it’s not just a Russian idea, this obsession with trees. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer thought that beauty had something to do with resisting gravity, and thus that trees (and other plants) were naturally beautiful to our human eyes.

…the law of gravitation seems in vegetation to be overcome since the plant world raises itself in a direction which is the very opposite to that of gravitation. The phenomenon of life thus immediately proclaims itself to be a new and higher order of things. We ourselves belong to this; it is akin to us and is the element of our existence; our hearts are uplifted by it. [emphasis mine]

And so it is primarily that vertical direction upwards whereby the sight of the plant world directly delights us. Therefore a fine group of trees gains immensely if a couple of long, straight, and pointed fir trees rise from its middle.3

When I first read these paragraphs by Schopenhauer (standing in yet another bookstore) I thought he was making an interesting point. It was memorable enough that I was able to find it again years later. I even thought it was beautiful.

But how bland Schopenhauer appears now against the backdrop of Shalamov’s larch tree! I would much rather stare at Pisakhov’s twisted little pines, at the gentle light in Romadin’s Volga landscape, or Borisov’s snow-covered forest fading into an infinite mist.

Николай Некрасов. “Мороз, Красный Нос.” https://www.culture.ru/poems/39553/moroz-krasnyi-nos

Varlam Shalamov. Resurrection of the Larch. Trans. Sarah J. Young. Cardinal Points. https://www.stosvet.net/12/shalamov/index3.html

Parerga and Paralipomena: Short Philosophical Essays. Translated from the German by E.F.J. Payne.-Rev. Ed. “Chapter XIX. On the Metaphysics of the Beautiful and Aesthetics.” (Oxford University Press, 1974).

It is such a Russian story. I like it very much.